First Series - Explaining my Thesis

Posted on Thu 08 February 2018 in Thesis

When you're a mathematics PhD student, your work is likely to be totally inscrutable to just about anyone you meet, even many fellow mathematicians. This is probably true for advanced research work in nearly any field, but I think the problem is especially bad in pure mathematics, largely for two reasons.

The first is that the the objects of study in mathematics are often unfamiliar and, to an outsider at least, hopelessly abstract. As a comparison, one of my brothers is also an academic, working on a PhD in biology and studying evolution in butterflies. The real details of his work are beyond me, but I learned the basics of evolution in high school, and I definitely know what a butterfly is, so he can tell me something about his work and I at least know what he's talking about. In contrast, my academic research involves various constructions related to quaternion-Kähler manifolds, and if you know what that means, congratulations to you on finishing your math PhD!

The second problem is that the way that mathematicians think about math, especially the way they do research, is very different from the way that many people learn about mathematics in school. If you stopped learning math in high school or in a first-year calculus course in college, you probably think of math as a collection of formulas to be applied to solving problems on a worksheet. But before those formulas can be used to solve problems, someone has to come up with them, and understand why they work. Even more crucially, someone has to build the logical framework that gives the formulas and their applications context. This is what mathematicians actually do -- they define different abstract logical systems and try to understand their properties.

As a simple example, consider arithmetic, that is, addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Middle school students learn algorithms like long division to compute these operations, and then spend weeks doing worksheets where they divide various numbers over and over. This is important to be able to do, but a mathematician would want to ask more questions: for example, what is a number, exactly, and what does it mean to multiply two numbers? A mathematician might notice that multiplication is an operation that takes in two objects from the collection of numbers and produces a third number, subject to various rules - for example, commutativity (that \(a \times b = b \times a\)) and distribution over addition (that \(a \times (b + c) = a \times b + a \times c\)). They might then try to consider other collections of objects and construct multiplication-like rules for those collections. In particular, the quaternions, which feature prominently in my thesis, are a number system constructed by the mathematician William Rowan Hamilton in the process of trying to find a way to "multiply" triples of numbers. Thinking about these abstract structures and trying to deduce their properties is, to a mathematician at least, far more interesting that doing worksheet after worksheet of long division problems.

This post is the first in a series that will ultimately attempt to explain the results of my thesis to a general audience (or at least my family, who might be the only people who ever read this). I hope not only to explain the esoteric and abstract objects that I spend most of my time thinking about, but also to demonstrate the way that mathematicians think about math.

Before embarking on that journey, though, I'll give the shortest summary of my work that I can. It's common advice for academics of all types to always have an "elevator pitch" explanation of their research that they could give to anyone in under two minutes. Mine goes something like this.

The Two-Minute Summary

I work in differential geometry, an area of mathematics that studies how to measure distances in spaces, and how spaces can themselves curve and bend. One of the most familiar geometric spaces is a flat, 2-dimensional, infinite plane - basically like a sheet of paper extended out as large as conceivably possible. High school geometry is really the study of this one space - learning about angles, distances, shapes, etc.

There are other spaces that one can study, though, with different geometries. As an example, consider the surface of the earth, which (if we imagine that the earth is perfectly smooth) has the geometry of a "round 2-sphere." It is also a two-dimensional geometry, in that you can specify a location on the surface of the earth using two numbers, latitude and longitude, and all the same concepts of geometry still apply - you can still talk about distances between points, angles, shapes on this surface, etc. It is very different from the flat geometry, though. For example, you could (in principle) continually walk in a fixed direction, and in doing so walk around the whole world and end up back at your starting point, which is definitely not possible on the flat plane.

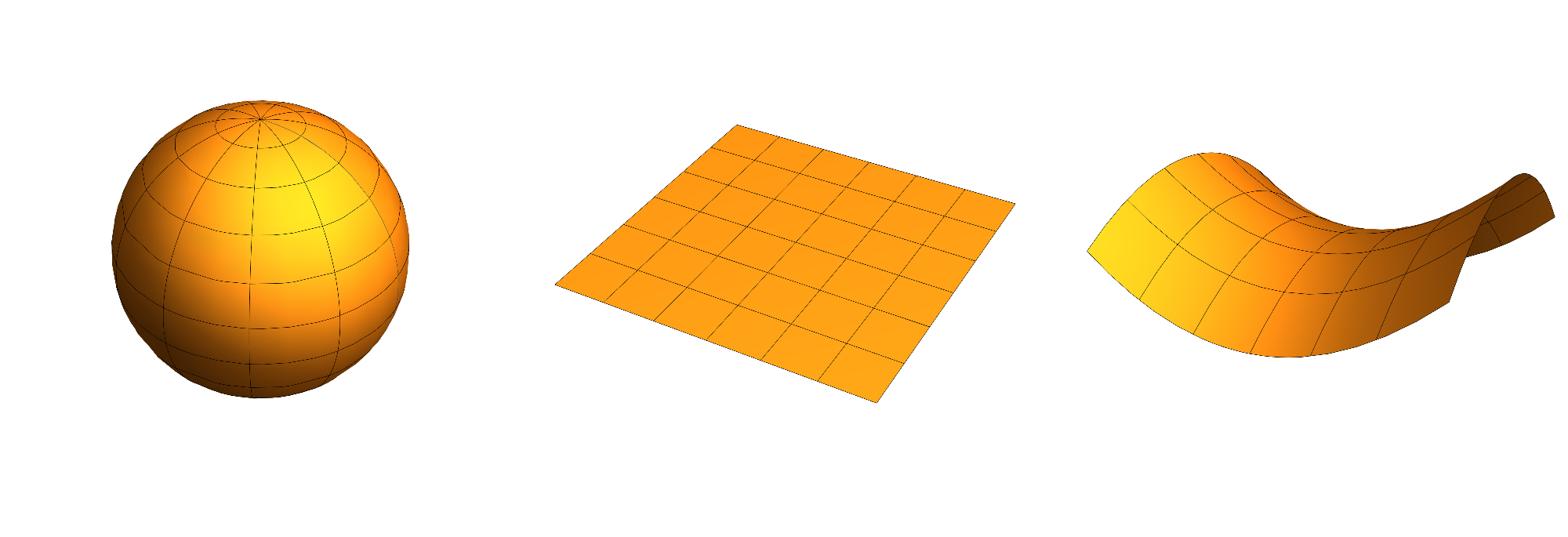

The main difference between these two geometries is a property called curvature. In two dimensions, there is a number that one can assign to every point of a space that describes how curved that space is at that point. For the flat piece of paper, that number is 0 for every point. For the sphere, that number is positive at every point. In fact, if \(R\) is the radius of the sphere, then the curvature is given by \(1/R^2\). For example, the curvature of the earth, which has a large radius, would be a small, but positive number. This agrees with our perception that the earth seems flat when you walk around, and that you'd have to walk a long way to notice it curving. If you could walk around on the surface of a smaller sphere, like a basketball, you'd definitely notice the curvature. There are also two dimensional spaces of negative curvature. "Negative" curvature just means that the surface curves in opposite directions. An example is the surface of a horse saddle -- the surface curves down to the ground on the left and right (where your legs go), but curves up to the sky in front and behind. A sphere always curves in the same direction.

Examples of 2-dimensional surfaces with positive, zero, and negative curvature

These concepts are easy to visualize for two-dimensional surfaces sitting in three-dimensional space (as illustrated above), but most geometry research is concerned with higher dimensions, where things are much more complicated. According to general relativity, for example, the universe is a four-dimensional geometric object, with the three familiar spatial dimensions and an extra time dimension, and the way that this "spacetime" curves determines the gravitational field. The concept of curvature is also more complicated in higher dimensions, where one needs many numbers to describe the curvature of the space in the many possible different directions, instead of the single number necessary in two dimensions.

As stated above, I study "quaternion-Kähler manifolds." These are higher-dimensional geometries, occurring in dimensions divisible by 4 (i.e., 4, 8, 12, ...) that have a very particular type of curvature, that makes them interesting in various mathematical applications and in theoretical physics. My work on these spaces is an attempt to understand both how many different types of quaternion-Kähler manifolds exist and how these spaces can be used to construct other geometries with interesting curvature properties.